This article is an adaptation of this speech.

David, Saul, and the Gibeonites

15-07-2025 - Posted by Geert-JanOriginally posted on June 25, 2025 – by André Piet

A forgotten story, rediscovered

The account from 2 Samuel 21 is little known — even among many familiar with the Bible. That’s not surprising, because it’s a charged and bloody story that, at first glance, feels strange and uncomfortable. But if you look beyond the moral surface, you discover a prophetic and rich testimony of God’s faithfulness to His promise.

David is confronted by a three-year famine. When he seeks the face of JAHWEH, he receives a remarkable answer: the famine is the result of a blood-guilt resting on the house of Saul, because he had killed the Gibeonites.

Joshua’s oath and Saul’s sin

The Gibeonites were Amorites — not Israelites — but they had, under false pretenses, placed themselves under the protection of Israel when Joshua entered the land of Canaan. Despite their deception, Israel had sworn an oath in the name of JAHWEH to spare them (Joshua 9). Centuries later, Saul broke that oath. In his zeal for Israel and Judah, he tried to eradicate the Gibeonites.

Though this event is described nowhere else in the Bible, God treats the broken oath with utmost seriousness. A vow made in His name is non-negotiable. It is holy. And so a curse rests on the land: no rain, no blessing.

Doing justice to a promise

David summons the Gibeonites and asks what he can do to effect “atonement.” In Hebrew, the word used isn’t the common shalom-sense “atonement,” but kafar — “to cover.” It refers to covering the curse, to end the blockade imposed on JAHWEH’s inheritance.

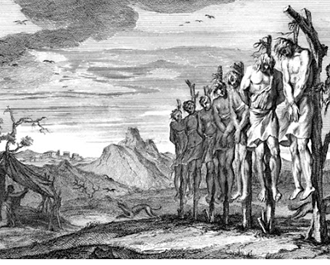

The Gibeonites refuse gold or silver, and they don’t seek revenge. They demand that seven male descendants of Saul be handed over to them to be hanged in Gibeah, Saul’s residence. In this way, they say, justice will be done for the wrong done to them.

David agrees, though he spares Mephibosheth — Jonathan’s son — because of a previously made oath. Seven other descendants of Saul are hanged in Gibeah, on a hill, “before the face of JAHWEH.”

Rispa’s mourning and the end of a dynasty

Rispa, mother of two of the executed, guards the bodies of the seven men. She spreads her mourning garment on the rock and protects the corpses day and night from birds and animals. Her devotion and grief act as a protest: the law demanded that those hanged be buried the same day (Deut. 21:23). Rispa honors the bodies — and thus the hope of resurrection.

When David hears what Rispa has done, he orders the bones of Saul, Jonathan, and the seven men to be gathered and buried in the family tomb in Benjamin — their tribal inheritance. Only then does the rain come, and the famine ends.

Typological lines: what this story truly speaks

When we understand this history typologically—just as Paul does elsewhere (Gal. 4:21–25)—Biblical “watermarks” become visible. Below are seven striking aspects:

- The house of Saul as symbol of the old covenant

Saul became king because the people wanted him. He reigned before David, just as the old covenant operated before Messiah’s coming. His zeal without insight (Rom. 10:2) led to death. In his attempt to do right for Israel, he broke the promise to the Gibeonites. - Gibeon as symbol of the ekklesia

The Gibeonites were not Israelites, yet they received a promise. So too the ekklesia — the church — gentile in origin, without right to Israel’s inheritance, yet possessed of divine promises. Gibeon means “elevated place” — a type of the church’s heavenly position in Christ. - First the promise to the ekklesia must be honored

Before God blesses Israel again, justice must be done to the Gibeonites. Likewise in salvation order: the church receives the blessings of the new covenant first; then Israel. - The end of Saul’s house linked with harvest time

The seven men die “at the beginning of the harvest”—a moment in time that points to the resurrection of Christ as the firstfruit (Lev. 23:10–11; 1 Cor. 15:20). In the midst of death and judgment, the light of new life shines. - Rispa’s honor to the bodies

Her care confirms God’s intention to raise the dead. In scripture, a body is not mere “corpse,” but a seed sown with expectation of resurrection (Concordant: 1 Corinthians 15:42–44). - David acknowledges burial in the inheritance

Saul’s house’s remains are buried in the land promised to them — an act of faith in God’s word. Burial place matters because God will keep His word. - Then comes rain: blessing follows justice

Only when justice is upheld — promise honored, bodies respected, order restored — does the rain arrive. A picture of divine blessing descending after righteousness.

Conclusion

At first glance, this story is dark, bloody, and difficult. But precisely in the darkness of the old covenant we see the outline of the light. Like a shadow that reveals the form of a body to come, this story points forward to the Messiah, the new covenant, the ekklesia, and the blessing that comes when the people return to God.

It’s not a moral lesson, but a divine testimony: God fulfills His oath. He honors His promises, even to those with no rightful claim. He does justice — through the cross — and grants new life in His time.

Thus this dark tale also proclaims the gospel of God.

English Blog

English Blog